If you’ve ever watched Shark Week you might think that the life of a shark researcher is full of adventure involving close death-or-life encounters with sharp teeth and snapping jaws. The reality looks different, U of T undergraduate student Vinky Wang and recent alumna Jessica Long know. It requires a lot more true grit than thrill.

Rather than swimming with the sharks, the two students spent hours hunched over their computers, cleaning, analyzing and visualizing data from observations of sharks in their natural habitat. The data set was supplied by the Shark Lab, a research unit studying the ecology of marine animals at the California State University, Long Beach.

Under the supervision of Vianey Leos Barajas, assistant professor at the Department of Statistical Sciences and the School of the Environment, Wang teamed up with Shark Lab researcher Jack May to answer the question of how changes in water temperature impact the behaviour and livelihood of Leopard Sharks along Southern California’s Coast.

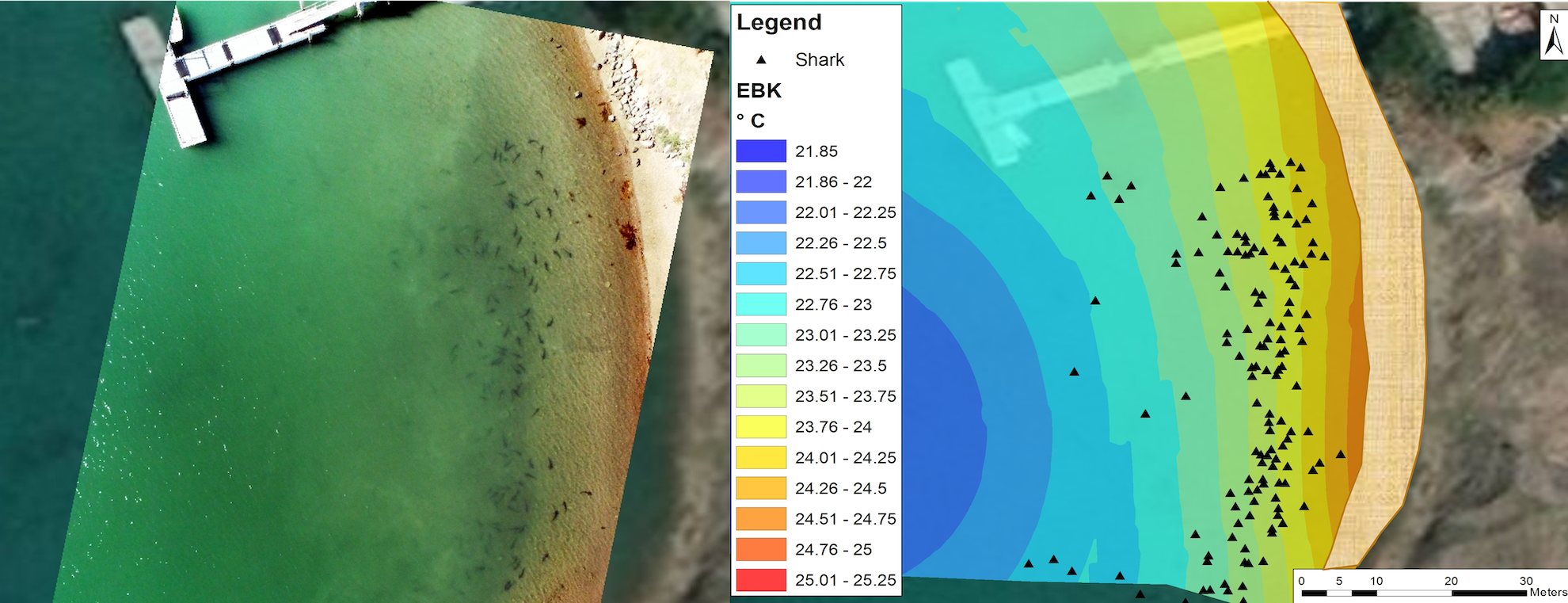

“The data is basically just a bunch of longitude and latitude coordinates and the number of sharks observed,” explains statistics, geography and math student Wang. “After you fit your statistical model and print out your output, you basically just have a lot of numbers. We then created a visualization that mapped all the coordinates, so you can see a map of the study region. You can see how the sharks move within each grid cell and where they prefer to aggregate and cluster.”

Preliminary findings show that Leopard Sharks are rather picky when it comes to water temperature. After analyzing the data collected by May over two summers, it seems that Leopard Sharks seek out areas in a specific range of temperature. They might prefer to hang out in one spot but don’t hesitate to move on to greener pastures if temperatures change and end up falling below or above the sharks’ preferred range.

With scientists ringing the alarm bells about climate change – most recently through a groundbreaking Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report released earlier this month – the importance of leveraging data to understand the impact of environmental changes on marine animals, is a vital tool in protecting our oceans and its inhabitants, May knows.

“The better we can understand how temperature affects sharks distribution and behaviour, the better we can manage them and make sure they have a healthy population for some time to come,” he says. “Statistics and coding play a huge role in that. With better technology comes better data and as researchers, we need to know how to make sense of that.”

Long, who recently graduated with a bachelor's degree in statistics, math and economics, spent her summer working alongside Shark Lab researcher Emily Meese on a similar project, analyzing the movements and behaviours of California horn sharks.

The most challenging part of her work was learning how to use “hidden Markov models” (HMMs), a complex statistical approach frequently used to model biological sequences and reveal patterns in animal behaviour.

“I had no prior experience with HMMs, so I had to read through textbooks and papers to get an understanding of what to do. It was a huge learning curve. Using statistics to study and classify animal behaviour in general is actually quite complex,” says Long. “I learned a lot through this project, and I really enjoyed teaming up with people in the field and learning about their work.”

Wang’s and Long’s research projects are part of Leos Barajas Bayesian Ecological & Environmental Statistics (B.E.E.S.) research group. The group’s goal is to develop statistical methods to help answer pressing ecological and environmental questions.

Leos Barajas emphasizes that working in interdisciplinary teams is a key component for all B.E.E.S projects and an important factor in student learning, as well as statistical research in general.

“What I’ve seen this summer is that pairing students with researchers from other disciplines has worked very well,” says Leos Barajas. “Statisticians alone can't make sense of the data. We need to work with experts in other fields to really understand what it is we’re doing.”

As for next steps for Wang’s and May’s project, the team is currently working on expanding their model to include data from other locations and see if there are other factors than just temperature that might affect the sharks’ behaviour.

“I find it rewarding to be able to apply the skills I learned in class to real-life data and to see results that have actual meaning and implications,” says Wang. “The thought, that this project might lead to more research and make a real difference, is just really motivating.”