The opioid epidemic ravaging the United States has claimed a staggering number of lives, but a clear picture of how the crisis has changed over the years – and who it currently affects the most – is surprisingly hard to find.

One popular narrative paints the opioid epidemic as a rural, low-income phenomenon, concentrated among Appalachian states – a claim that might be largely rooted in stereotypes, says Monica Alexander, an assistant professor in the department of statistical sciences and the department of sociology.

She decided to put the theory to the test.

Just a couple of months earlier, Alexander had published a paper that unravelled another myth surrounding opioid deaths in the United States.

“I was inspired by a New York Times article on how the opioid epidemic was mostly affecting white people. That turned out to be false. The data showed that the current number of opioid-related deaths is increasing at a higher rate for Black people,” says Alexander (pictured left).

“I was inspired by a New York Times article on how the opioid epidemic was mostly affecting white people. That turned out to be false. The data showed that the current number of opioid-related deaths is increasing at a higher rate for Black people,” says Alexander (pictured left).

“We were curious to see if there are other standing narratives that aren’t quite accurate, and to find out how things have actually changed.”

In search of a clear picture of how opioid-related deaths are distributed across the United States, Alexander teamed up with three other researchers at Stanford University and Harvard University. The team wrangled close to 20 years' worth of data on causes of death in the U.S., revealing the changing face of one of America’s biggest public health crises in the process.

Their study appeared in JAMA Network Open last month.

Here are some of the most important findings:

The crisis is growing – and fast

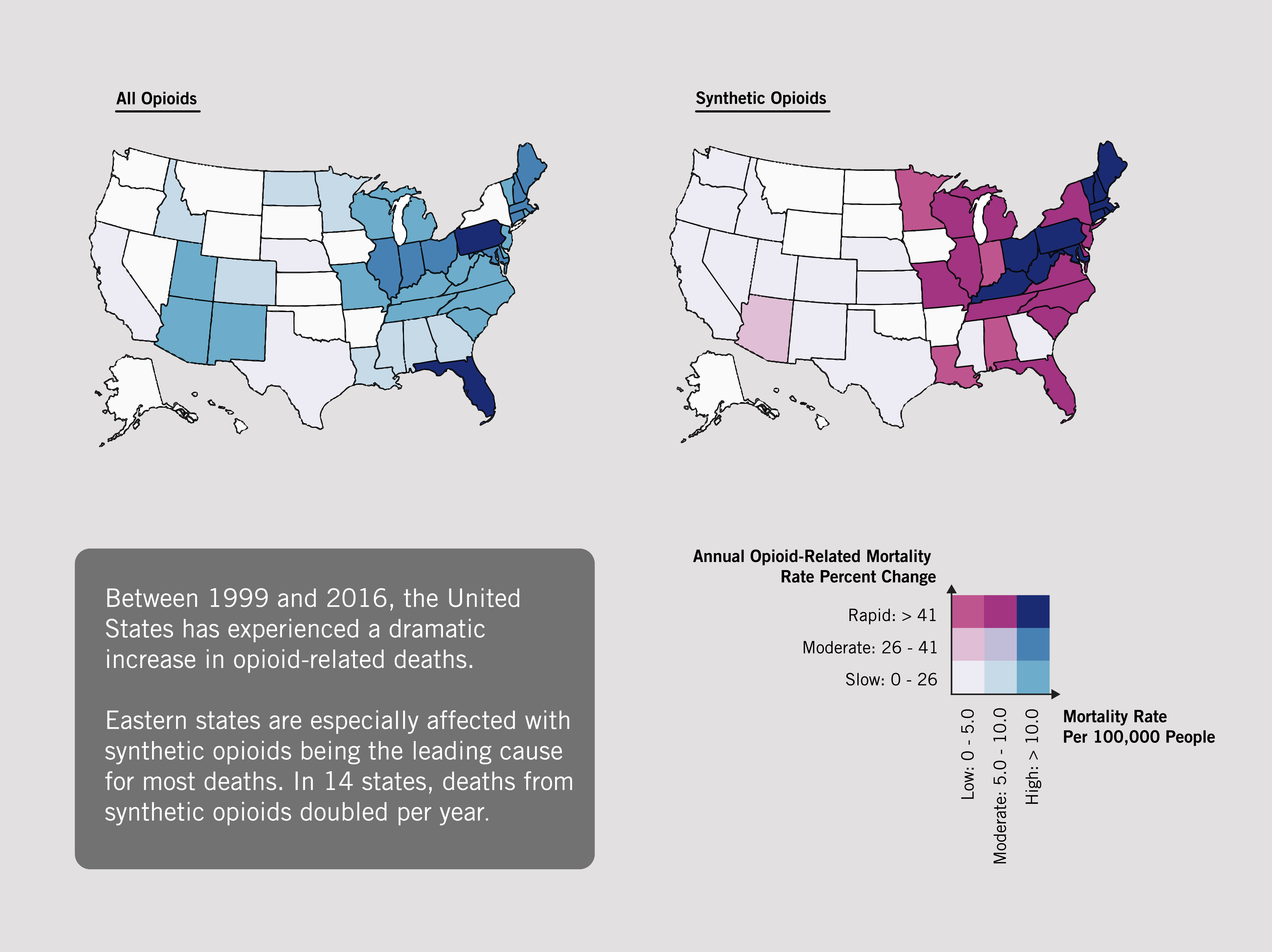

The opioid crisis has grown exponentially, the research found, with the number of opioid-related deaths quadrupling over the last two decades.

Within 18 years, more than 351,500 men and women died from opioid-related causes in America. In states with high opioid-related death rates, such as New Hampshire and West Virginia, the opioid crisis has reduced overall life expectancy at age 15 by a full year.

“What that means is that if – hypothetically – you would get rid of all opioid deaths in a state, people’s life expectancy would increase by one year,” says Alexander. “Just to put that into perspective: Changes of 0.1 years over a year are considered normal.” That makes life expectancy loss from opioids greater than that from either firearm or car accidents in most of the U.S.

The crisis has spread

Long believed to be concentrated among Appalachian states and parts of the Midwest, Alexander’s research shows that the crisis has spread. Eastern states have seen a sharp rise in opioid deaths – with Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Massachusetts, Maryland, Maine, New Hampshire and Ohio among the states with the highest rise in opioid-related deaths.

Synthetic opioids are the main culprit

Synthetic opioids now by far outnumber heroin deaths in most eastern states. In 28 states, opioid-related deaths from synthetic opioids doubled every two years. In half of those states, deaths doubled every year.

While prescription pain killers, such as oxycodone, led the first wave of the opioid epidemic, illegally manufactured synthetic opioids, mainly fentanyl, have taken over as the leading cause of death.

Fentanyl is a particularly potent synthetic opioid. Up to 100 times stronger than morphine and many times more potent than heroin, a barely visible amount of fentanyl powder can be lethal. Among drug dealers, lacing drugs with fentanyl to save money has become a popular practice, and it is putting drug users at risk for accidental overdoses.

There are many reasons why some U.S. areas are harder hit than others, says Alexander. Differences in drug supply between western and eastern states might be one of them.

“West of the Mississippi, you see heroin sold mostly in the form of black tar heroin, which is hard to mix with other drugs. East of the Mississippi, you mostly see white powder heroin, which is very easy to lace with synthetic opioids,” she says. “It’s impossible for drug users to just look at it and determine if this is just heroin or heroin laced with something much deadlier.”

To help policy-makers take active steps, Alexander and her team highlighted several public health interventions in an open access paper released in late February, such as expanding access to naloxone, putting needle exchange programs in place and increasing support for people suffering from mental health issues and addiction.

“Prevention is obviously the goal but looking at the data I don’t think we can just rely on prevention. In my opinion, there needs to be a widespread focus on treatment and easy access to treatment,” says Alexander.

“We are at a point where this is an emergency. Something needs to be done if we want to prevent even more people from dying.”